For thousands of Connecticut citizens now in jail, the right to a speedy trial has become a cruel joke

[Excerpt from Fairfield County Weekly, Nov. 21-27, 1997]

By Jayne Keedle

On Jan. 14, 1993, Kenya Brown was arrested and charged with shooting Vincent Broadnax in the leg. Brown, who at the time was 15 years old and living with his girlfriend, Yolanda Zayas, claimed that Zayas’ ex-boyfriend Carton Watson pulled the trigger, but that Boradnax was to afraid to identify Watson as the shooter and fingered Brown instead. The one witness who was prepared to testify was Zayas.

On Sept. 14, 1993, public defender Miles Gerety moved for a speedy trial. His motion was granted, which meant that within the next 30 days Brown should have appeared in court. But on Oct. 13, 1993, 30 days following the motion, Gerety was involved in another criminal trial and could not take the case. Bridgeport Superior Court Judge Richard Damiani chose to exclude the time that Gerety was unavailable from the 30-day period during which the case, by law, should have come to trial.

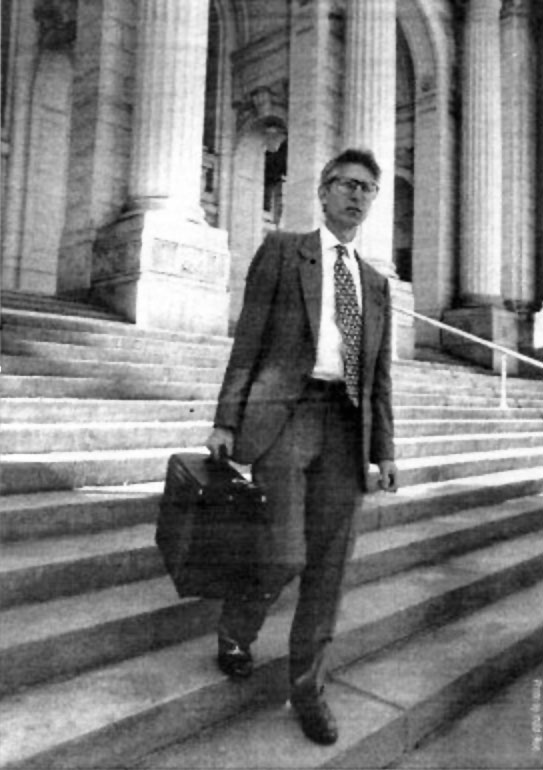

His attorney, Robert Sullivan, takes issue with Damiani’s decision – and for good reason. Brown’s trial was delayed until Oct. 25, during which time Zayas, a key witness in the case, died. Brown was convicted of attempted second-degree assault and sentenced to 12 years, suspended after eight. Sullivan contends that if the case been tried within 30 days, according to the statue, the outcome could have been quite different.

Judge Damiani told Sullivan that the time Brown’s public defender was working on another trial stopped the clock on the final countdown towards a trial date. He noted that there were 113 potential speedy trial cases before the Bridgeport court at the time, probably 90 percent of which were represented by public defenders, many of which would qualify for dismissal under the law if the time the attorney’s spent at other trials could not be excluded. Sullivan, however, maintained in his brief to the state’s Supreme Court that “dismissal of the case is precisely what the Legislature intended.”

As Sullivan interprets both the statute and the debate surrounding it, the Legislature intended to use the dismissal clause in the bill to give the judicial department the ability to come back and seriously lobby for greater funding of prosecutors, public defenders and the like to make sure speedy trial rights were protected.